A New Era for Transfusion Medicine: Through Carefully Planned Leadership Transition, Fast-Growing Section Stays True to Patient-Focused Mission

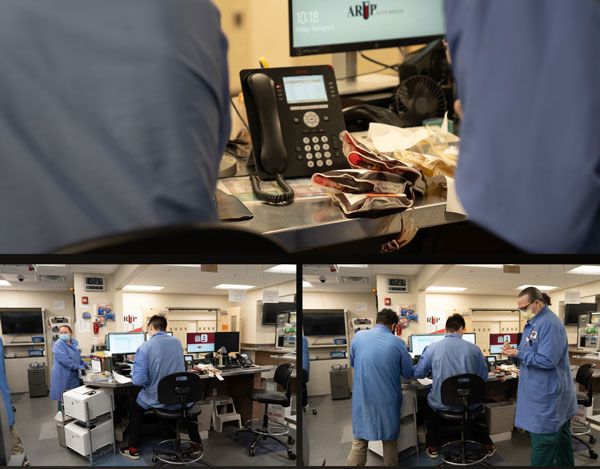

On a recent morning, the Blood Bank at University of Utah Hospital resembled any other laboratory. Medical laboratory scientists wearing full personal protective equipment (PPE) worked bent over their benches while a handful of colleagues typed on keyboards or talked on telephones nearby.

Then an alarm sounded with shrill beep, beep, beeps. It looked as if someone had stepped on an anthill as people scattered in all directions. In less than five minutes, they had selected and prepared blood products—four units of O-negative blood and two units of plasma—for delivery to the emergency room (ER) for a Trauma 1, or a critically ill or injured patient. Then it was back to other tasks, at least until the next alarm.

Day in and day out, these laboratorians save lives, and they know this. Without the therapeutic product they provide, patients will die. That’s why they’re here.

Seldom, though, is the lifesaving power of their essential product and the work they do more apparent than when one among them has the chance to meet the likes of Luccas Borges.

A little more than two years ago, Borges, a lifelong skier, was descending a slope at Deer Valley Resort when the binding on one of his skis snapped. The ski flew off, and his efforts to regain control while careening at an estimated 50 miles per hour failed. Borges collided with a ski-lift column, sustaining what is commonly referred to as a “handlebar injury,” characterized by a focal blow, which severed a branch of his aorta and caused other severe abdominal trauma.

What happened next was nothing short of miraculous. The resort’s ski patrol responded immediately, followed by Park City Fire District emergency medical technicians, who cared for Borges while he screamed in pain and later lost consciousness as an ambulance raced him to the U ER. In the hours that followed, Borges hovered near death. Toby Enniss, MD, FACS, Ram Nirula, MD, MPH, Alexander Colonna, MD, MSCI, FACS, and dozens of their colleagues challenged the depths of their broad expertise and experience to save him. A determined Enniss remained at Borges’ bedside through that harrowing first night.

In all, the medical team drew on 85 units of red blood cells, 78 units of fresh frozen plasma, and 14 units of platelets to sustain his life, using nearly every unit of product matching his blood type that the Blood Bank had available.

Borges, a 25-year-old Harvard University graduate and master of business administration student at the University of Chicago, proved to be a fighter. Slowly, astonishingly, he began to improve, when few thought he would survive his horrible injuries.

Borges is thriving, even though he remains on a difficult road to full recovery as he awaits a small intestine transplant. In early February, he returned to Utah for the first time since his accident to participate in a review of his case and to thank the large medical team that saved him.

“To say my survival was miraculous discredits your work,” he told the first responders and U hospital emergency personnel gathered for the case review. All around, members of the medical team shed tears—of relief, empathy, shared purpose, and pride. “Thank you. Truly,” Borges said as he wiped away tears himself. “Thanks so much to all of you.”

Luccas BorgesTo say my survival was miraculous discredits your work. Thank you. Truly.”

Trauma survivor

The Patient, First and Foremost

Before Borges, Kelly Cail, MT(ASCP), had met only one other survivor in person in her 21 years working for ARUP Laboratories’ Transfusion Medicine section, where she is now operations director, yet Borges and others like him are the reason she specialized in the field and never once considered doing anything else. “We see the benefit of what we do for patients every single day.”

Her commitment is mirrored throughout the Transfusion Service and Blood Services, even as the Transfusion Medicine section is at an important inflection point in a carefully planned and orchestrated leadership transition.

In February 2023, Robert Blaylock, MD, retired after more than 35 years as medical director for the Transfusion Service, Blood Services, and the Immunohematology Reference Laboratory (IRL), but only after working with colleagues for five years to transition the departments. Ryan Metcalf, MD, CQA(ASQ), joined ARUP in 2017 as a medical director and became section chief of Transfusion Medicine in 2021.

Blaylock created a culture of teamwork that was built on his unwavering commitment to patients and their safety, Cail said. That culture is intact, as both new and longtime employees remain loyal to his ethos.

“Doing the right thing was so important to Rob,” she said. “He was not one to send an email or wait for someone to return a call. If there was something that needed attention, he would go right to the ICU [intensive care unit] or to the executive offices and make sure the need was understood.”

“Because of Dr. Blaylock, we understand and have a great appreciation for the importance of our jobs,” added Candace Thomas, a blood component specialist who, like Cail, has worked in Transfusion Medicine and the Blood Bank for 21 years.

During Blaylock’s tenure, the section grew in complexity and sophistication as U of U Health added hospital beds and expanded services. The number of patients who underwent transfusions from 2002 to 2022 increased 60% to 5,475 in the 2022 fiscal year alone. Red blood cell transfusions increased 44% to 16,418, while platelet transfusions increased 210% to 7,098.

In all, Transfusion Medicine now has about 125 employees working at the U Hospital and Huntsman Cancer Institute, donor centers in Salt Lake City and Sandy, and the IRL at ARUP, and traveling daily to numerous mobile blood collection sites.

Planning for the Future

Cail said demands on the section will only continue to increase with the opening in mid-2023 of the Kathryn F. Kirk Center for Comprehensive Cancer Care and Women’s Cancers, which will add 50 beds to Huntsman. The number of red blood cell transfusions is projected to increase by 8% and the number of platelet transfusions by 19%.

The need for blood products and transfusion services has increased with each addition to the University of Utah Health system.

See map location

See map location

See map location

See map location

See map location

See map location

See map location

See map location

See map location

See map location

See map location

See map location

U of U Health also intends to add a West Valley Health and Community Center in late 2026 or early 2027, for which she and Metcalf already are planning.

As section chief, Metcalf has hired Waseem Anani, MD, as medical director of the IRL and Blood Services, and Steven Baker, MD, PhD, and Erica Swenson, DO, both associate medical directors of Transfusion Medicine.

Metcalf also continues to build on initiatives already in place to optimize use of blood products, which he noted are among the “most overused in medicine.”

“As always, patient safety is paramount,” Metcalf said. “Within that context, our goal is to provide the right product for the right patient at the right time for the right reason.”

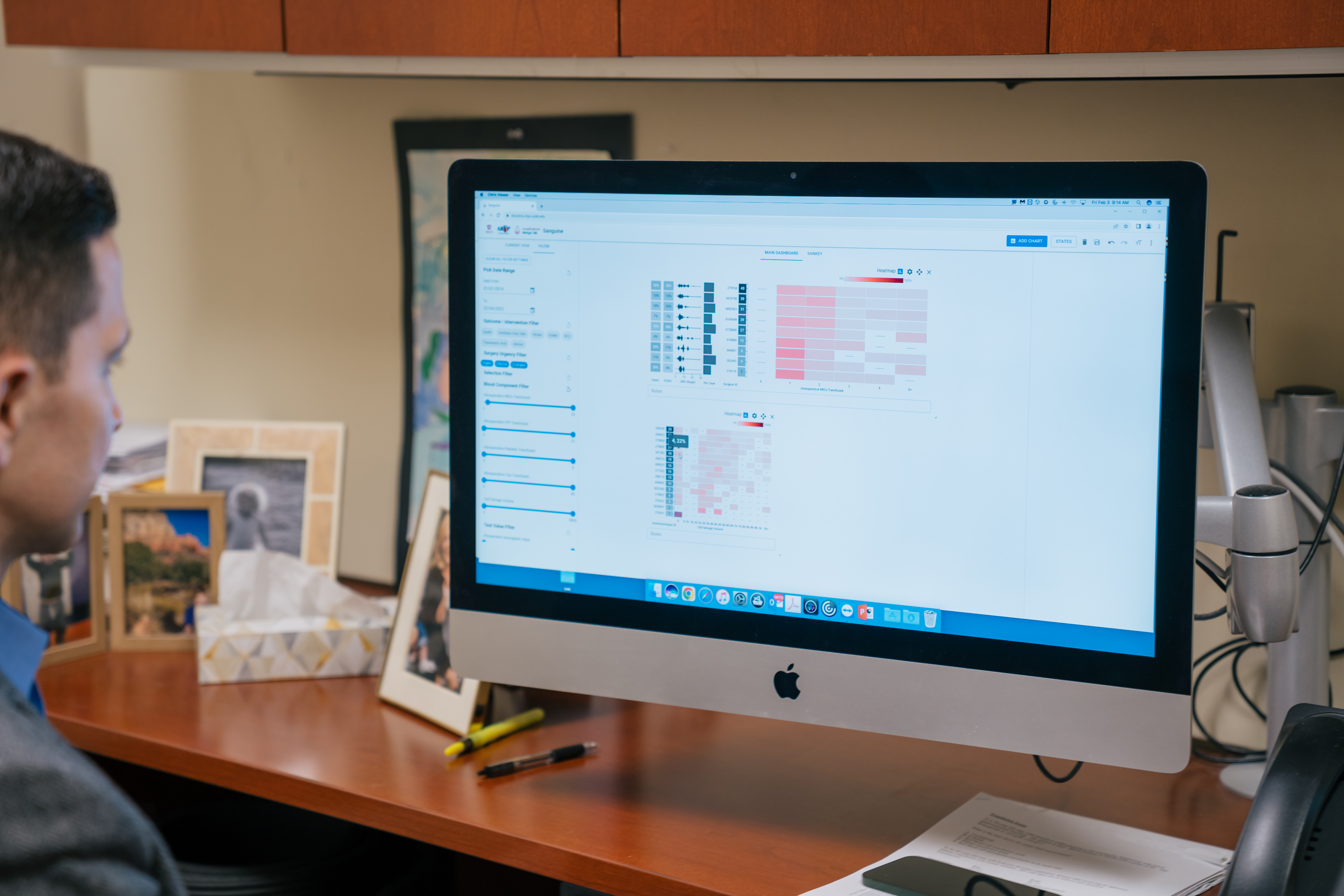

An expert in data-driven/informatics approaches to patient blood management, he and colleagues throughout the U of U Health system are using data to better understand the many factors that influence how blood products are used. Often, the data reveal information that can lead to more efficient use of blood and better patient care.

They are working to reduce complexity and add precision to blood product ordering and transfusion practices and to decrease the time it takes to get the right products to patients. They also continue to perform research and evaluate the research of others on whole blood and other emerging blood therapies to ensure that ARUP is offering the best blood products.

“We want to foster a culture of continuous improvement that is blame free as we improve processes,” Metcalf said. “It has been fun to show that we’re able to use data to get better and better over time.”

Boosting Collections to Meet Demand

He said the improvements are better for patients, but they also make the section more resilient to blood shortages, a consideration that is ever more important given the challenges of collecting enough blood products to meet the demand for transfusion services. From 2009 to 2022, for example, collection of units of red blood cells by ARUP Blood Services decreased by 16%.

Managing the inventory of blood products is a daily challenge for the Blood Bank. A single serious accident, such as that which injured Borges, can quickly deplete the supply, said Tyler Anderson, DPT(ASCP)CM, a blood inventory specialist. When it happens, he is spurred into action, contacting ARUP’s donor centers and, if necessary, searching outside ARUP to procure what’s needed.

“We never want to have to tell a patient a surgery will have to be postponed because we don’t have the blood that would be needed,” Anderson said.

Boosting collections is another prerogative of Metcalf, Anani, Cail, and their colleagues. A creatively aggressive outreach program that educates communities about the importance of blood donation to increase collections is more important than ever.

One effort, for example, will focus on raising awareness in West Valley City in advance of the opening of the U’s new health center there as part of a goal to encourage blood donations in communities near where the blood products will be used, Cail said. ARUP Blood Services is also expanding its digital capabilities to engage donors by allowing as much flexibility as possible in scheduling donations and redeeming rewards.

Borges said he knows he never would have survived his accident if it hadn’t been for the dozens of blood donors whose gifts were used in his care. He shares his story broadly with the hope that it will help inspire more blood donations.

“So many things could have gone very differently for me, but there were so many people who made it possible for me to continue living, to continue writing my story,” he said.

Laboratorians are used to being behind the scenes, to “hiding in the basement,” where many hospital labs—and the U Hospital Blood Bank—are located, said Sheila Villanueva, CLS, a lead medical laboratory scientist. She said it’s rewarding when their efforts are called out, and when it’s recognized how stressful and unpredictable their jobs can be as they do their part in the race to save lives.

Her work, her team, and the sense of purpose she feels when she hears stories such as Borges’ have kept her at the Blood Bank for 28 years.

“When you talk about loyalty, I have it. I just love being part of what we do here,” Villanueva said. “I will be here for the rest of my career.”