A Singular DNA Destiny Decoding the Beauty and Hardships of Life

In the painting, a colorful DNA helix streams out of the palm of Logan’s hand—a fist surrounded by auras of blue and green, as well as light. In reality, this young man’s four-fingered hand is typically gripping a paintbrush, applying rich strokes of acrylic paint to canvas, as Logan Madsen attempts to capture in art the unique characteristics of his body as well as his personal struggles with the way he was born.

“I’m expressing pride in my challenges,” says Logan of this painting, titled “Born This Way.” “It’s a forceful, almost angry pride, in looking different and being different and having a point of view that no one else has.”

While all DNA is unique, Logan’s is especially singular. He was born with not one, but two rare genetic conditions: Miller syndrome and primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD). Miller syndrome causes facial and limb malformations—intelligence is not affected. PCD is a rare lung disorder that affects the cilia, the tiny, hair-like structures that line the airway and carry mucus and bacteria toward the mouth to be coughed or sneezed out. PCD interferes with Logan’s breathing and makes him prone to respiratory infections.

Logan is one of only 30 people documented to have Miller syndrome. His sister, Heather, is one of those 30. She was born with PCD, as well. The chance of two siblings being born with these two rare conditions? Approximately one in 10 billion. The odds of winning the lottery are significantly higher.

Because of these unlikely odds, Logan’s family (his mother Debbie, his father Terry, and Heather) caught the attention of geneticist Lynn Jorde, PhD, and his colleagues. “Ever since we learned about Debbie’s children in our genetics clinic in 1981, we were all curious about their condition. The syndrome was just being defined by Marvin Miller,” recalls Jorde, who is now chairman of the University of Utah Health’s Department of Human Genetics.

As DNA sequencing technology evolved and its cost dropped significantly, these scientists’ thoughts returned to Logan and his family. “We thought, why not sequence a family that has a disease with a cause we don’t know, since the sequencing might reveal the cause of the disease?” says Jorde. (Years after learning about Logan and Heather, Jorde would end up on a blind date with their mother, Debbie, and eventually marry her. It was likely the only first date in which the words “postaxial acrofacial dysostosis” popped up in conversation.

In 2010, sequencing ultimately identified the genetic “errors” that cause PCD and Miller syndrome. This discovery was also a seminal step forward in human genetics because it revealed the human mutation rate, which helped pave the way for the Utah Genome Project. (See related story Unsolved Cases.)

The team also learned that Debbie carries a disease-causing version of the cystic fibrosis gene, so both her children carry it as well. However, since their father is not a carrier, the children have only one copy and therefore do not have cystic fibrosis.

The chance of having all three of these characteristics—PCD and Miller syndrome gene variants and the cystic fibrosis gene variant—is one in 300 billion. “There is no one else like Logan and Heather on the planet,” says Debbie. Heather and Logan also have autism, which was diagnosed when they were both in their twenties.

Miller syndrome is an autosomal recessive genetic condition caused by mutations (changes in the DNA code) in the DHODH gene. Children inherit Miller syndrome when each of their parents has a mutation in the DHODH gene, which results in the children receiving two copies—a double dose. PCD is associated with a recessive gene as well and must be passed on by parents who are carriers.

“Although there are many rare genetic disorders, collectively they may be present in approximately 3 percent of the world’s population,” says Chris Miller, one of ARUP’s 16 genetic counselors.

“There are several benefits of determining the cause of a rare disorder. Parents who have children with the same disorder can be connected, even internationally, with one another and support each other through life’s journey,” says Miller. Determining the cause of their child’s disorder enables parents to learn their chance of having another child with the same condition and allows researchers to begin developing targeted treatments for the condition.

Born This Way

Buried in Logan’s DNA is also the capacity to develop arresting art (his family tree has been traced back to Vincent van Gogh), a lively intellect, and a deeply compassionate nature. Perhaps because tasks of daily life take longer and are more arduous for him, he observes the activity around him with a keen eye.

“ I believe everybody could be classified in the DSM-5*… We’re all struggling with something, because we’re all human.”

–Logan Madsen

For a while, a parade of ants marched into Logan’s kitchen, until he finally put a stop to it. “Have you ever noticed how an ant acts once it’s removed from the group, from its community of fellow ants?” he asks. “It’s confused, then stands up on its back legs, and looks around, like ‘where did everyone go?’ i felt bad for it,” said Logan. “i took that one outside.”

In his small apartment/studio, the necessities of his daily life—dozens of medicines, supportive cushions, tools to jerry-rig or make ergonomic adjustments—are mixed in with hundreds of acrylic paint tubes, canvases, rags, and brushes. His dog, a Chihuahua-mutt mix, navigates the cluttered terrain.

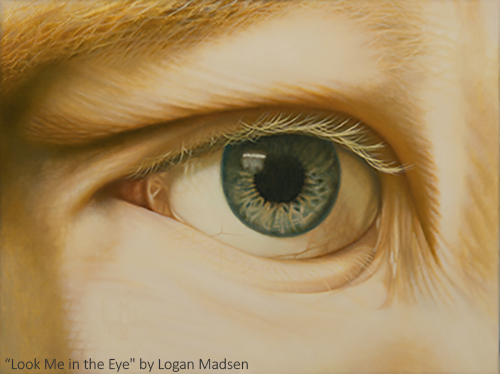

Logan’s painting “Born This Way” defines his “Syndrome Psychology” series, which Logan has been working on for more than 10 years and has had exhibited a number of times. The series captures the characteristics of Logan’s body and his emotional mindset. In “Helpless,” he lies prone, ribs exposed, clutching the back of his head. In “Love What Makes You Different,” Logan’s right eye—an eye that has undergone five surgeries—stares out at the viewer through a heart-shaped tunnel he makes with his hands. Logan has endured 24 surgeries in his life, so far.

“People stare, so I wanted to make paintings so people could stare all they want,” says Logan. “Call it an offensive stance.” Before this series, Logan was known for his robust, close-up paintings of individual flowers—a viewer so close might be tempted to sniff for a floral scent. “At my core, I’m colorful, bold, and powerful. That is why I gravitated toward flowers,” says Logan. “I’m also a hopeless romantic.”

When Rarity Strikes Twice

“I didn’t think they would live through childhood,” says Debbie. When Heather was born in 1977, it was immediately obvious something was wrong. Her arms were exceptionally short and her wrists were bent at a 90-degree angle. Initially, physicians thought she had Treacher Collins syndrome because of her facial characteristics (underdeveloped cheekbones, abnormally small jaw, cleft palate, cup-shaped ears, drooping lower eyelids). When Heather was 18 months old, a geneticist determined that it was Miller syndrome (then known as postaxial acrofacial dysostosis). There were only three other documented cases in the world at the time.

When considering whether to have a second child, Debbie and her husband Terry (since divorced) were assured by a geneticist that the chance of having another child with Miller syndrome was one in a million—and probably even lower than that because it had already happened. Just to be sure—and to prepare herself—Debbie had an ultrasound in the seventh month of her pregnancy. “You’re going to have a healthy baby girl,” she was told.

On April 1, 1980, the doctors delivered an 8-pound, 6-ounce baby boy with the same short arms and bent wrists that Heather had at birth. “It was shocking in a different way than when Heather was born. It was almost surreal,” recalls Debbie. Not long after, her pediatrician slapped her on the leg and said, “Congratulations, you just made medical history.” No other family existed that included two siblings with Miller syndrome. This was the case until 1988, when another family in New Zealand had a second child born with Miller syndrome.

From that point on, every second of Debbie’s life would be devoted to caring for Heather and Logan, her only children. Her marriage to Terry buckled, then broke. The children’s care required feeding tubes, constant doctors’ visits, surprise hospitalizations, and repeated surgeries. Medical bills piled up.

"I already have the intellectual stimulation, which I provide myself. What I need is a friend who can provide the emotional connection that reminds me I am human and compassionate and shows me that it is enough to just be me."

—Heather Madsen, excerpt from Eight Fingers and Eight Toes: Accepting Life’s Challenges

Debbie’s story of caring for two children diagnosed with rare diseases is remarkable in its own right and is documented in a film about Logan (“Logan’s Syndrome”) and in a book she wrote with her daughter Heather (Eight Fingers and Eight Toes: Accepting Life’s Challenges). Exhausted, worried, and overwhelmed as a single mother, Debbie eventually learned to take one day at a time, one challenge at a time. “When you start looking into the future and worrying about what might happen, you will find yourself quickly depressed."

"I knew that if I couldn’t find happiness, how could they?” says Debbie.

For years, she grappled and soul-searched for a way to accept her life—a far different life than she had imagined for herself. Slowly she came to a place of peace and acceptance. “When you are not worried about the future or dwelling on the past, you have more space to find and feel what is good in life, and focusing on this space is what became important to me.”

To Logan, explaining what it is like to live with a rare condition and the chronic pain that comes with it is like trying to explain what raising children is like to a childless person. “It is a part of every single moment of your life. You can’t help but hope each next moment will be better than the last.”

Logan has had to find his own way through his challenges and emotions, which inevitably find their way into his paintings. He says, “I live—and keep wanting to live—by magnifying all the little granules in life on a daily basis so they overwhelm and dwarf the hard parts.”

This approach to life is not unlike Logan’s approach to the flowers he paints. His canvases, filled with the deep colors and textures of petals and pollen and delicate stamens, vastly magnify those minute details, giving viewers an opportunity to forget their own difficulties for a moment.

* DSM-5 is the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

To see Logan’s paintings, visit: www.loganmadsenfineart.com

HOME

HOME