Advancements in Immunogenicity Testing

Deliver Relief to Patients with Autoimmune Diseases

In order to keep dancing, she kept pushing through the joint pain. Then one morning, she couldn’t even walk; her body was not allowing her to put any pressure on her feet. Looking back, Lisa Foley recalls this moment vividly because it halted her plans to move to L.A. and give professional dancing a shot. And it was the beginning of her life with rheumatoid arthritis. She was 22.

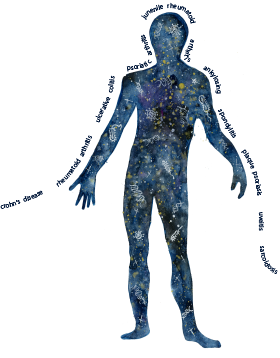

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is an autoimmune disease, more specifically a non-infectious inflammatory disease. Other diseases in this category include inflammatory bowel disease, Lupus, and psoriasis, to name a few. Inflammation results from the overproduction of several proteins in the body, including one known as tumor necrosis factor (TNF).

What happens is the body starts seeing the medication as a foreign element, triggering the immune system to create antibodies to eliminate it. This is called immunogenicity. This happens in about half of the patients.”

Julio Delgado, ARUP Chief Medical Officer

TNF’s primary role is regulating immune cells ( white blood cells) that protect your body against infectious disease and foreign invaders. To manage the overproduction of TNF seen in rheumatoid arthritis, patients are prescribed TNF blockers, medications that suppress the response to TNF and decrease inflammation.

These medications, referred to as biologicals, are made of naturally occurring molecules. TNF blocking drugs don’t always work because the body may see them as foreign invaders, producing antibodies against them that make the drugs ineffective.

Testing for drug levels of biologicals help clinicians figure out if the drug is still working for the patient and if it is being administered at the right dose. “This can lead to a more personalized approach to treating patients with autoimmune diseases who aren’t responding to treatment, which of course improves patient care and saves time and money,” explains Julio Delgado, MD, MS, ARUP’s chief medical officer and formerly medical director of Immunology. He recently co-authored an article on this topic in the journal Clinical Chemistry with ARUP colleague Eszter Lázár-Molnár, PhD, medical director, Immunology. Both hold faculty positions at the University of Utah School of Medicine.

When Foley was diagnosed, TNF blockers were not yet available. “They first started me on steroids, then some other pretty potent medications,” she recalls. To have children, Foley had to go off the medications. Three months before her second child was born, the first TNF-blocker came on the market (1998). Since then, she has been on three different TNF blockers. “It works for a number of years then my body starts rejecting it. At first you think it’s the be-all, end-all drug; then, the body plateaus,” says Foley, who kept on dancing whenever she could.

“What happens is the body starts seeing the medication as a foreign element, triggering the immune system to create antibodies to eliminate it. This is called immunogenicity,” explains Delgado. “This happens in about half of the patients.” He explains that when a patient has been responding to a drug, then stops all of sudden, the physician wants to know why.

If the patient has developed antibodies against the drug, the physician may switch them over to another type of TNF blocking drug. There are five of them available in the United States, with one biosimilar recently approved. When the patient develops antibodies against the TNF blocker, it is important to switch to another drug, as the patient could end up with an immune-complex disease that threatens the organs.

Immunogenicity testing may also reveal that there are no drug antibodies present, indicating that the patient may require a higher dosage. “We are the only lab that offers a test that specifically identifies the production of neutralizing antibodies against TNF blockers; a situation in which TNF blockers become functionally ineffective,” says Delgado. There are antibodies produced against TNF blockers that are non-neutralizing and these antibodies can disappear over time, which doesn’t require the need to switch to another TNF blocker.

Drs. Delgado and Lázár- Molnár developed a test that helps clinicians figure out if the prescribed medication is still working for a patient with autoimmune diseases and if it is being administered at the right dose. Such precision medicine improves patient care and saves everyone involved time and money.

Lázár-Molnár explains that the most commonly used tests measure the presence of any antibody that can bind to the drug molecule, regardless of whether or not they interfere with drug activity. The ARUP test only detects the presence of those antibodies that inhibit the function of the drug, which makes it more specific for identifying the cause as to why the drug treatment is not working.

ARUP developed immunogenicity testing after being approached again and again by clinicians and hospitals looking for a method that was as good or better than what was already being offered by other laboratories but less cost heavy. Patients were being hit with expensive testing bills, some thousands of dollars, on top of already expensive medications.

“So far when doctors have not seen an improvement in the patient, they have increased the dose or frequency or switched to another drug,” says Lázár-Molnár. This approach can be time-consuming. “This more personalized approach using laboratory testing is likely to be more cost-effective and reduce delays in finding the right treatment, which is important considering TNF antagonists are among the most expensive prescription drugs.”

It works for a number of years, then my body starts rejecting it. At first you think it’s the be-all, end-all drug; then, the body plateaus.

Lisa Foley, mother and dancer

It’s been 17 years since Foley first started taking TNF blockers, and she continues to live her life on her terms. “I make my choices based on quality of life—I want to live life as normally and fully as possible,” expresses Foley. “I’ve always believed in making the best of what I have right now.”

HOME

HOME