A career that has traditionally been overshadowed by more visible healthcare professions is suddenly in the spotlight because of the world’s interest in coronavirus testing.

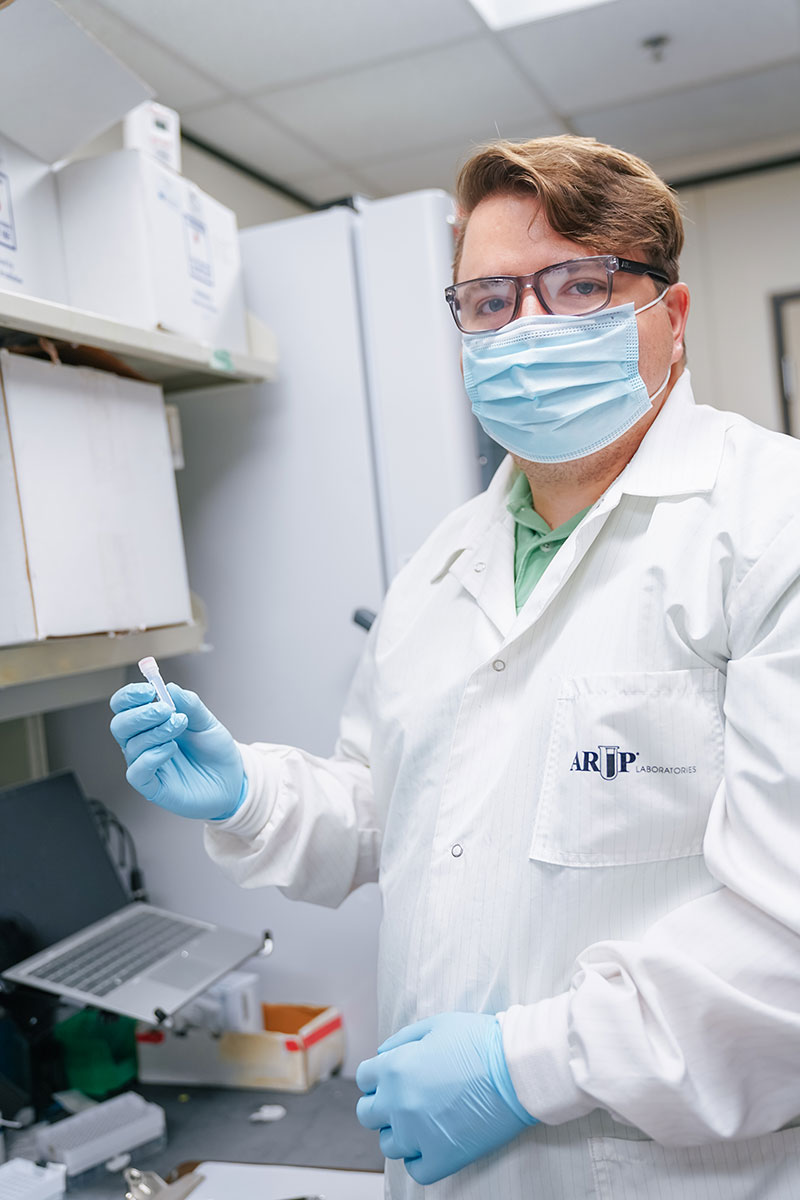

Medical laboratory scientists who work in hospital labs and in national reference laboratories such as ARUP are the inconspicuous, less visible participants in helping to diagnose patients.

And these scientists are in demand. “At ARUP, we’ve had to come up with unique and creative ways to work with our employees and grow them into medical laboratory scientists because there are just not enough to fill all our positions,” says Karen McRae, student education coordinator. Approaches to increase the number of staff members with medical laboratory science (MLS) degrees include a partnership with Weber State University’s MLS program, on-site training and education, and tuition reimbursement for employees who complete MLS degrees.

About six and half years ago, Jeffrey Clifford started in the Microbial Amplified Detection Lab and then earned a Medical Laboratory Science (MLS) degree through the University of Utah’s MLS program using ARUP’s tuition reimbursement program. He had an undergraduate degree in biology and a minor in chemistry when he started at ARUP. Today, Clifford is an MLS lead in the Molecular infectious Diseases Lab.

This career path can be ideal for anyone who is fascinated by science and wants to help patients, but not necessarily work directly with patients. Laboratory work requires strict attention to detail, tenacity, and repetition, according to McRae, who has worked in a number of labs throughout her career.

“In a lot of labs, it is the repetition that ends up making you an expert,” McRae says. “You start recognizing what is normal and what is not. You recognize patterns and small changes that may be important clues to a disease or illness.”

“It’s like a puzzle. In microbiology, you are trying to figure out which organism is in the sample, and there is a process involved in trying to figure it out,” says Jeffrey Clifford, an MLS lead in the Molecular Infectious Diseases Lab at ARUP. “The machines in our lab aren’t like a black box where I don’t know what is going on. I know on a microscopic level what is going on.”

Educational Pathways for Laboratory Scientists

The most direct educational path to working in a lab entails earning an MLS bachelor’s degree, which can take up to five years and requires clinical laboratory experience. The final step after graduating is to pass a nationally recognized certification test, such as the one offered through the American Society for Clinical Pathology. Those with MLS degrees are sometimes referred to as medical laboratory technologists or med techs.

Most states have at least one university or college that offers an MLS program. Utah, home to ARUP, offers four. Some institutes offer MLS master’s degree programs, as well, which often attract students with undergraduate degrees in the sciences. Colleges sometimes call MLS programs allied health, clinical lab science, or medical technology programs.

Medical laboratory technicians (MLTs) can also work in laboratories, usually performing the same testing as those with MLS degrees but without supervisory duties. MLTs have a two-year associate’s degree in MLS.

MLS degrees expose students to a variety of areas, with rotations in hematology, molecular diagnostics, immunology, urinalysis, microbiology, chemistry, parasitology, toxicology, immunohematology (blood banking), coagulation and transfusion, and laboratory safety and operations. Additional accreditation may be required to specialize in a specific area, although a lot of learning happens through on-the-job training.

Research & Development (R&D) scientist Buck Lozier circled back to earn his MLS certification. He started at ARUP with a bachelor’s degree in microbiology, working as a technologist trainee in the Autoimmune Immunology Lab. Within a year, he earned certification as an immunology technologist and then pursued a master’s degree in laboratory medicine and biomedical science, all while working at ARUP. The master’s degree provided him the opportunity to develop and improve lab tests, including, most recently, COVID-19 antibody testing. Lozier eventually went on to obtain his MLS certification.

“I’m a mechanic by nature and worked as one through my undergraduate years,” says Lozier, who grew up taking machines apart and reassembling them. “I don’t like to let broken things or problems sit. Basically, my job here is to fix or improve lab tests. And in the process, I get to work with experts—our medical directors—who are at the top of their fields. I learn something new every day.”

Part of the Diagnostic Team

Laboratory science as a profession has been around since the 1930s, although it has changed dramatically over time. According to McRae, the profession originally attracted women who were interested in medicine but didn’t want to be nurses and believed that there was little opportunity for them to become physicians or scientists. Now the occupation is similar to nursing in gender balance and attracts both men and women. “Our biggest challenge is awareness. The profession is so behind the scenes that many don’t even know it is an option,” McRae says.

In addition to working in hospital or reference labs, many in the medical laboratory sciences work in doctors’ offices that have small labs, or in R&D at biotech companies or for lab equipment manufacturers. The size of the lab can often determine the breadth or depth of duties and necessary skills. For example, in a rural hospital lab, a laboratorian may work in blood banking (ie, prepare blood products) as well as check someone’s cholesterol or identify pathogens that make a patient sick. In contrast, at a national reference laboratory such as ARUP, a laboratorian might only perform molecular infectious diseases testing or work exclusively in the parasitology lab, analyzing specimens from all over the country.

Like many healthcare jobs, laboratory science work requires a variety of shifts so that labs can provide around-the-clock testing. While this can mean working weekends or holidays, the career also offers flexibility for a variety of schedules.

In seventh grade, Marlee Croft considered being a marine biologist, a nurse, a microbiologist. She knew science was her path. Then her aunt, who worked in a laboratory, gave her a tour to see what it was like. “I could really see myself working in a lab,” recalls Croft. When she hit college, she went straight for an MLS degree from BYU. She was done in five years and now works as a float specialist in ARUP’s Infectious Diseases Division.

Depending on the type of lab, laboratorians may be working with specimens such as blood, tissue, sputum, urine, fecal matter, saliva, sweat, cerebral spinal fluid, joint fluid, ocular fluid, bone marrow, amniotic fluid, and even parasites. Each specimen is linked to a patient and may hold vital clues to the patient’s condition. Laboratorians are the detectives who help providers treat their patients appropriately.

“What we’re doing in the lab is all about the science behind the medicine,” says Marlee Croft, MLS, who is a float specialist in the Infectious Diseases Division. Croft always knew science was her path. When she discovered laboratory medicine, she pursued an MLS degree at Brigham Young University.

“People often don’t know it, but we are part of a patient’s diagnostic team. There is a strong sense of accomplishment working in the lab when you know the results are needed and wanted.” Croft, along with Clifford, was involved in the first massive wave of COVID-19 testing at ARUP.

While lab automation has increased dramatically over the past two or three decades, tests cannot be performed without the hands-on skills and knowledge of laboratorians. “This is not just about putting a tube in a machine and pushing a button,” McRae says.

Addy Kallas works in ARUP’s Specimen Processing and Receiving Department. She and her co-workers help label, sort, and track all specimens as they arrive and ensure they get to the appropriate lab. “I get to leave every single day knowing I have made a positive difference in so many people’s lives,” says Kallas, who has an undergraduate degree in psychology and sociology and is considering pursuing a MLT or MLS degree.

Medical laboratory scientists are constantly conducting correlation and validation tests to ensure that equipment is working accurately. Laboratorians are juggling multiple kinds of tests, using different methodologies and instrumentation across a variety of diagnostic medicine disciplines.

Although nurses, doctors, and phlebotomists may be collecting the specimens, laboratory professionals must thoroughly understand the collection and transportation requirements necessary to ensure that each specimen is viable for testing.

While laboratorians are generally not the type to seek out the spotlight, they appreciate that their profession is being recognized for its important role in helping to diagnose patients.

“Now when people get their blood drawn, they will realize that someone is testing it,” says Katie Olson, who works in ARUP’s Immunology 1 Lab. “They will realize it’s not the doctor, or the nurse, but that there is someone else involved in their care. That’s us.”

For additional information on a career in the medical laboratory sciences, visit the American Society for Clinical Laboratory Science.