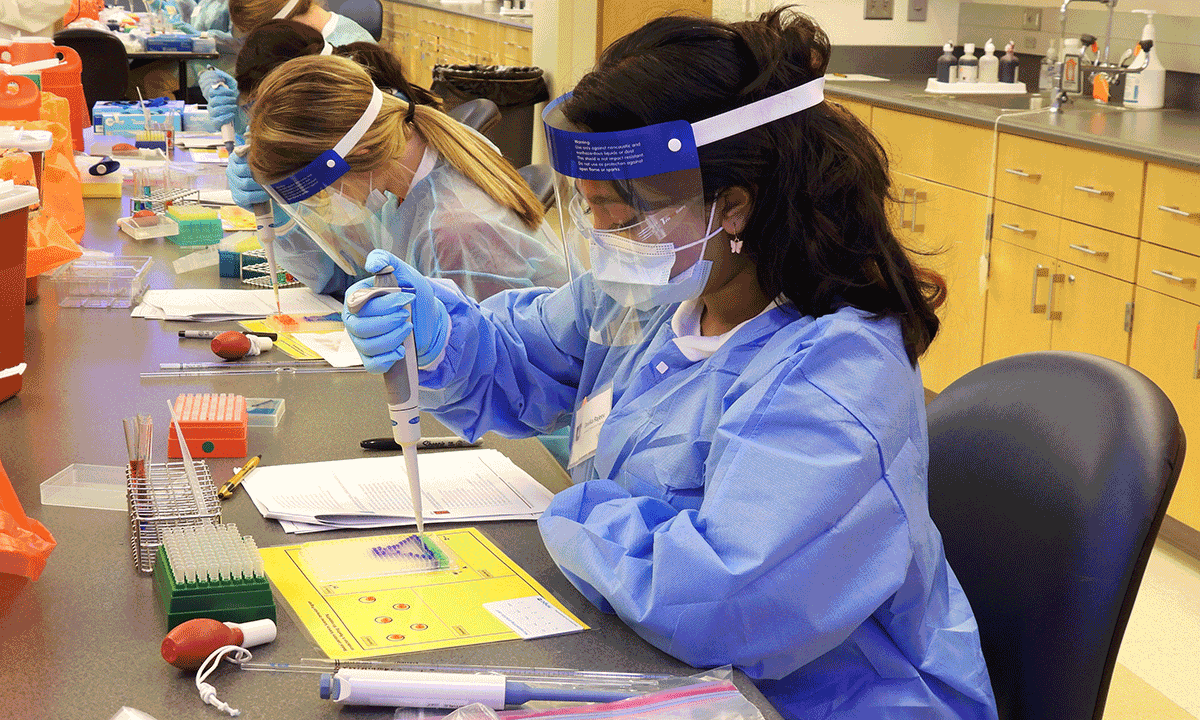

Students practice pipetting skills during the first laboratory medicine summer camp held by the Division of Medical Laboratory Sciences in the Department of Pathology at University of Utah Health.

Photo credit: Adriana Callahan

In an effort to promote interest in careers in laboratory medicine, the Division of Medical Laboratory Sciences in the Department of Pathology at University of Utah Health recently conducted a weeklong immersion program for high school students. It was the first summer camp in medical laboratory sciences at the U of U Spencer Fox Eccles School of Medicine.

“There is a real nationwide shortage of medical laboratory professionals who perform clinical diagnostic testing,” said Lacy Moss, PhD, MLS(ASCP)CM, an assistant professor of pathology who chaired the committee that oversaw the development of the immersion camp. “So, we wanted to get the word out to high school students that this can be an exciting career, similar to nursing or pharmacy, that they might want to explore.”

In Utah alone, there are ample job opportunities for those who pursue careers in laboratory medicine. Salt Lake City-based ARUP Laboratories, for example, employs more than 4,600 people who work in the company’s more than 70 labs. A nonprofit enterprise of the U Department of Pathology, ARUP performs tests for hospital and health system clients in all 50 states.

Valuable Experience

In all, 32 Utah high school students with diverse backgrounds who were entering their sophomore, junior, or senior years were selected to participate from among 107 applicants.

Over the course of five days, the students participated in lectures and conducted hands-on laboratory testing using substances that mimicked real blood, urine, and other bodily fluids. They delved into the nitty-gritty of hematology, immunology, molecular diagnostics, blood banking, and other important aspects of medical laboratory science.

“I was surprised how much stuff actually goes into processing laboratory tests,” said Sabina Akelbek, a 16-year-old who will be a senior this fall at the Northern Utah Academy for Math, Engineering, and Science in Ogden. “Before I participated in the camp, I thought you get your blood drawn, it goes into a tube, and magically you get the results. In reality, people are overseeing these processes. Humans, rather than machines, are much more involved than I thought.”

Following her experiences at the camp, Akelbek, who wants to go to medical school, is considering pursuing a bachelor’s degree in medical laboratory sciences. And that is exactly what Diana Wilkins, MS, PhD, MT(ASCP), chief of the Division of Medical Laboratory Sciences at U of U Health, had hoped to hear.

“This camp was an opportunity to expose young students who haven’t chosen a career path yet to the possibilities medical laboratory testing offers and help spark an interest in pursuing it as a profession,” Wilkins said. “I was encouraged by how enthusiastic and engaged these students were throughout the week.”

Ten laboratory medical science faculty members led the students through the camp, teaching them about lab safety, pipetting, and other basic procedures before moving on to more complex testing simulations and case studies.

Students, for instance, analyzed simulated urine samples (made with water, salt, and yellow food coloring) with added compounds such as nitrites that, when tested, would suggest a patient had a urinary tract infection.

In another case, students evaluated imitation stool samples (potato flakes, baby food, and food coloring) for giardia, a parasite found in contaminated food and water that can cause diarrhea, nausea, and stomach cramping.

“Medical laboratory science is a good foundational major for students because it is a good stepping stone for other health professions,” Wilkins said. “I’ve always branded it as a mini-medical school because you learn a lot about how to conduct the tests, interpret what they mean, and contribute to accurate medical diagnoses.”

Setting Students Up for Success

Those who do choose to pursue a career in medical laboratory science after participating in the camp are likely to have a rosy future, Moss said. In fact, employment in the field is expected to grow by 11% between now and 2030, with about 26,000 new job openings a year, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. That growth outpaces the average for all other professions.

“Over the past five years, all of our graduating students were employed or had received job offers after completing our program,” Wilkins said. “That reflects growing demand and the nationwide shortage driving it.”

The camp attracted a diverse set of applicants from across the state of Utah. Overall, 42 of the 107 applicants were from historically underrepresented groups or rural areas. Of the 32 students who participated, 18 were from underrepresented groups. Travel stipends were available to students who were underrepresented, from rural areas, or were experiencing financial hardship.

Next year, summer immersion camp planners anticipate having a one-week session for at least 48 Utah high school students. Students will pay a $25 lab fee and receive all meals and laboratory supplies for the week. Although participating students will be responsible for their own housing and travel arrangements, travel stipends will again be available to facilitate program attendance.

Planners also hope to open the camp to participants outside the state of Utah. Organizers plan to begin accepting applications for the 2023 immersion camp in January. Additional details will be available soon.

Doug Dollemore, doug.dollemore@hsc.utah.edu