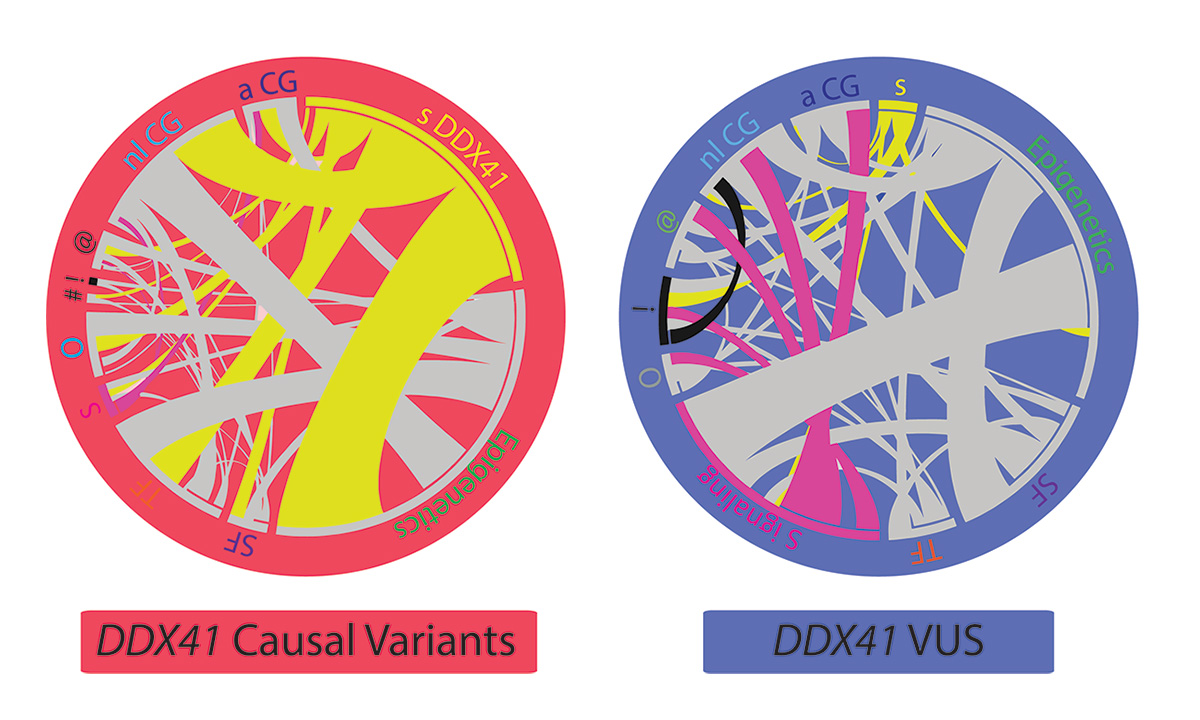

These images depict the distinct genetic profiles found in patients with pathogenic germline DDX41 variants and variants of unknown significance (VUSs).

A new study from ARUP Laboratories and six other universities maps the pathogenic variant landscape of inherited myeloid neoplasms and provides guidance on the diagnosis and clinical management of affected patients. The study, the first to chart and classify these genetic variants, deepens the understanding of a recently identified germline variant in DDX41, a protein-coding gene that is involved in hemopoiesis and has been implicated in inherited blood cancers.

The research article, entitled, “The genetic landscape of germline DDX41 variants predisposing to myeloid neoplasms,” was published in the journal Blood in August.

“By using the pathogenic variant landscape, we can provide an excellent guideline on how to diagnose and manage patients with DDX41-associated myeloid neoplasms,” said Peng Li, MD, PhD, medical director of Hematopathology at ARUP and a key researcher in the study.

Unlike most other inherited cancers, DDX41-related myeloid neoplasms, such as acute myeloid leukemia, often do not present until the sixth or seventh decade of life, which makes it challenging for researchers to determine the relationship between genetic variants and disease. Researchers identified germline variants in DDX41 as causal for myeloid neoplasms just six years ago.

Since then, investigators have found that DDX41-associated myeloid neoplasms are among the most prevalent familial myeloid neoplasms in the world.

In this study, Li and her colleagues examined archived data from 9,821 unrelated patients with hematologic malignancies across six different institutions in the United States, including the University of Utah, ARUP, Oregon Health and Science University, University of Kansas Medical Center, Emory University, Stanford University, and University of California, San Diego.

“We used different layers of evidence; the first layer was genetic profiling, the second was the characteristic pathologic and clinical findings, and the third was overall survival rates,” Li said. “We found that those who have the DDX41 mutation have relatively clean genetic profiles and don’t carry any other common somatic mutation seen in patients with acute leukemia and myelodysplastic syndromes.”

To determine the genetic profiles, researchers extracted DNA from fresh bone marrow aspirates and then tested the samples using a targeted next generation sequencing (NGS) panel that included 65 genes. The study identified 176 patients with at least one putative DDX41 germline variant who had been diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia, a myelodysplastic syndrome, or a myeloproliferative neoplasm.

Li and her colleagues identified 82 presumed germline variants, of which 39 were classified as causal variants and 43 as variants of unknown significance (VUSs). They also reported 53 novel germline variants and 13 novel somatic variants.

In addition to classifying the germline variants, researchers analyzed disease characteristics associated with each variant, as well as disease prognosis.

“Because mutations in different genes reflect different characteristics of the disease, we should provide a gene-specific guideline for those patients,” Li said. “We want every individual patient with a potential germline predisposition, regardless of the patient’s age, to have an accurate diagnosis and appropriate management.”

In addition to definitive diagnoses and direction for treatment, researchers discovered some good news.

“Previously, prognosis was considered poor, but we found that patients with this particular genetic profile actually have a better overall survival rate in comparison to those not carrying germline mutations,” Li said.

Findings from the study also suggest that these patients respond well to chemotherapy, and the benefit of bone marrow transplant engraftment is yet unclear.

According to Li, further research will need to focus on early detection of the disease and management of minimal residual disease. “We know that the patients won’t experience overt disease until their 60s or 70s, but prior to definitive diagnosis of a myeloid neoplasm, they experience years of cytopenia,” Li said. Additional considerations include when to begin screening for tumors in individuals identified with these genetic variants.

When asked about whether these variants always cause disease, Li responded, “That’s the million dollar question. The idea of inherited cancer is always very nerve wracking for patients because they know they were born with a mutation that predisposes them to a cancer. However, there may be individuals in the general population who carry this mutation without disease. Our screening tool alone is not powerful enough to determine whether this mutation is always pathogenic or whether an individual who carries a pathogenic variant will manifest disease.”

This research was also featured in a recent episode of the Blood Podcast.

Kellie Carrigan, kellie.carrigan@aruplab.com