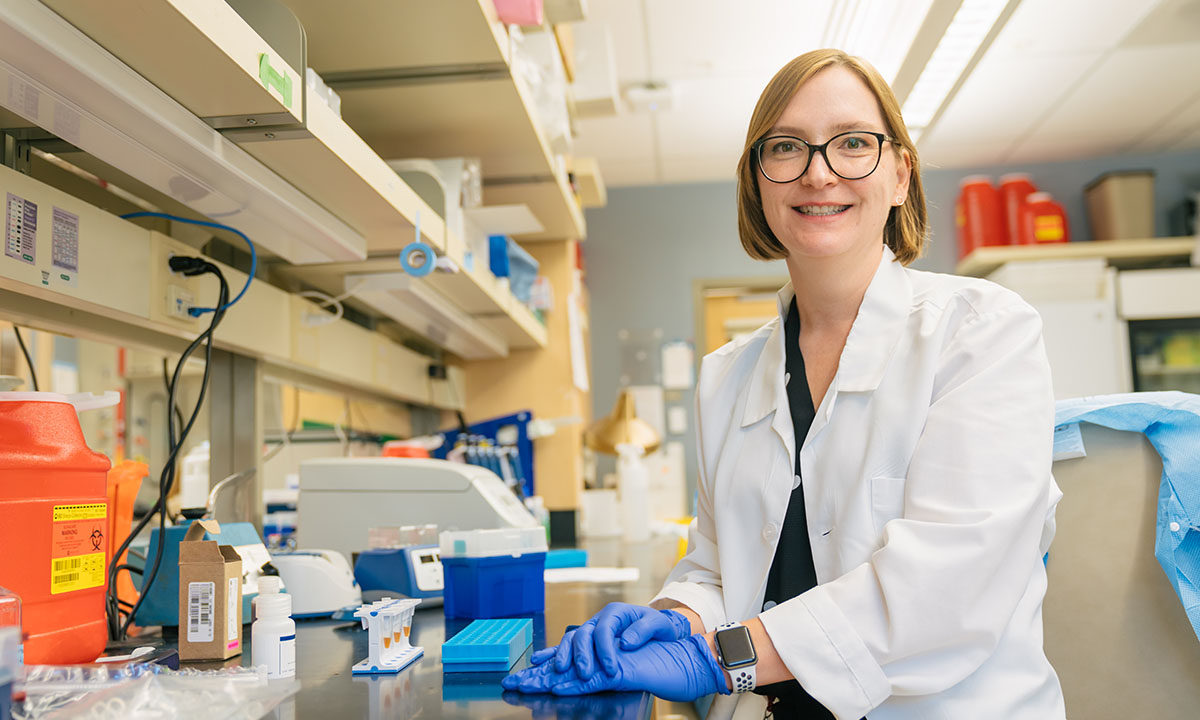

In her lab at the University of Utah, Allison Carey, MD, PhD, is using a molecular barcoding approach she developed to identify the genes that allow some strains of Mycobacterium avium to establish chronic infections and resist treatment with antibiotics.

An ARUP Laboratories medical director’s “big idea,” which could lay a foundation for the development of improved therapies for Mycobacterium avium and potentially other chronic bacterial infections, has earned her a prestigious grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) New Innovator (DP2) program.

Allison Carey, MD, PhD, ARUP medical director of Hematopathology and an assistant professor in the University of Utah School of Medicine’s Division of Clinical Pathology and Division of Microbiology and Immunology, will receive $1.5 million over five years to advance her research. Carey is using a molecular barcoding approach she developed to identify the bacterial genes that allow some strains of M. avium to establish chronic infections and tolerate prolonged exposure to antibiotics once infection is established.

DP2 grants are awarded to first-year faculty members with “big ideas, but without a lot of preliminary data” to help them get their ideas off the ground, said Carey, who had just joined the U and ARUP after completing a postdoctoral fellowship in microbiology at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health when she applied for the grant in October 2021.

“The grant is transformational for my research,” she said. “It’s a really nice runway for me to get my program accelerated.”

Carey developed and validated her molecular barcoding approach while at Harvard, using it to investigate strain-specific differences in M. tuberculosis. In M. avium, she saw an opportunity to study a bacterium that is more genetically diverse than M. tuberculosis, and also more difficult to diagnose and treat.

Like tuberculosis, M. avium can cause lung infections, but it also manifests as disseminated or soft-tissue infections, Carey said. Whereas tuberculosis is typically transmitted through close contact with an infected individual, M. avium is an environmental bug. “It’s everywhere. If you were to culture your showerhead, it would be there most of the time, but it doesn’t always lead to illness,” she said. “We’re constantly exposed, but not all strains of this bug are equally able to establish chronic infection.”

Carey added that some people are more susceptible to infection by more virulent strains of M. avium—those who are immunocompromised or have an underlying lung disease. Older people are also more vulnerable. “If you do happen to be unlucky enough to get an infection, it’s very hard to treat,” she said. “People think tuberculosis is bad because it requires a six-month treatment course with antibiotics; M. avium requires an 18-month course on average, and sometimes longer.”

In her research, whole gene sequencing is being performed on bacterial isolates, then Carey and her team are using computational analysis to identify pathogenic strains and nonpathogenic strains of M. avium. The researchers will also be conducting experiments in different infection models and in vitro to determine how different strains respond to antibiotics. “We’ll be trying to figure out which genetic variants are making some strains really hard to clear and others not so hard to clear.”

Carey said her collaborations with ARUP’s Mycobacteriology Lab and with Adam Barker, PhD, formerly ARUP’s chief scientific officer and now chief operations officer, and Salika Shakir, PhD, ARUP medical director of Microbial Amplified Detection, are critical to her research because it is through these collaborations that she gains access to genetically diverse specimens and to the expertise of Barker, Shakir, and others.

ARUP is among the nation’s largest providers of testing for M. avium and other bacterial infections. “I couldn’t have written the grant proposal without this collaboration,” Carey said. “It was specifically called out as an important feature of the grant by the reviewers.”

“DP2 grants are very competitive, and this is a tremendous accomplishment for Dr. Carey,” said Julio Delgado, MD, MS, ARUP executive vice president and chief of Clinical Pathology at the U.

He added that the grant will help foster an ideal situation for Carey as a physician scientist, and for ARUP, which thrives on its affiliation with the U and its commitment to continually advance laboratory medicine through the academic pursuits of its medical directors, all of whom are also U faculty members.

“Dr. Carey is showing how this is ideally done,” Delgado said. “She is a clinical laboratorian who is drawing on basic science to make important discoveries that will lead to improved patient care.”

Lisa Carricaburu, lisa.carricaburu@aruplab.com