My Life Was

Disappearing Before

My Eyes

The fatigue lingered after Chris caught strep throat. He reasoned that it was a combination of the exhaustion that comes with having a new baby and the effect of Minnesota’s bleak, winter days. Yet his weakness intensified. His arms trembled as he lifted his newborn daughter, so he compromised, lying on the floor with her.

By spring he was seeing double, short of breath, and his hands tingled. He started using a cane and wheelchair to get around. Still, no one knew what was wrong.

While Chris and his wife Alicia watched their newborn daughter, Taylor, gain weight and reach milestones, Chris’s lean, athletic build withered.

“Don’t sit on Dad,” Alicia would tell their 4-year-old son, Justin. “Don’t ask Dad to do it.” Justin would tug at his dad and plead, “Teach me how to ride a bike.”

“It was heartbreaking,” recalled Alicia. “He didn’t want to be remembered as the dad who lay around on the couch all day.”

Before the strep, Chris’s trajectory was enviable: 26 years old, he was fresh out of college, undertaking a brand new job as a medical technologist at the Mayo Clinic, and had a blossoming family. Then he got sick. And sicker. He took medical leave from his job. His intense pain kept him up at night, so he sometimes had only one or two hours of sleep. Walking exhausted him. His days consisted of moving from the couch to the bedroom or bathroom and back. Going outside was difficult. “Even the sun hurt,” Chris remembered.

A Medical Wild-Goose Chase

Over the next 18 months, a medical odyssey involving all kinds of diagnostic tests and well-intentioned specialists would challenge Chris and Alicia’s grip on hope. One physician ran tests and an MRI to check for multiple sclerosis. When Chris experienced what felt like a panic attack and rapid heart palpitations, a cardiologist ordered a cardiac panel and multiple other tests to check for heart issues. When he lost 10 pounds and then developed a distended belly, the physician ordered diagnostic and imaging tests, looking for cancer or tumors. When he experienced hot flashes and swollen lymph nodes, an infectious disease specialist ran more tests. They proved nothing.

A neurologist ran a battery of tests and concluded that the illness was in Chris’s head: He was depressed. A psychiatrist diagnosed him with agoraphobia, general anxiety disorder, and depression, although Chris disagreed with all three diagnoses. To address the loss of mobility, doctors prescribed physical therapy. He “failed out” three times, nearly fainting from the exertion the therapy required. Eventually, Chris’s medical record would run 300 pages in length and include results from hundreds of lab tests.

The thermoregulatory sweat test, which Chris dubbed “the Easy-Bake Oven test,” involved being coated in gold-colored powder from head to toe and heated up in an enclosed space. Everywhere he sweated, he would turn blue. “I looked like a Smurf,” recalled Chris. This test can diagnose certain neurologic and autonomic disorders. Still nothing.

“Sometimes people’s bodies don’t react the way a textbook says they should react. And often, patients have a phenomenal sense of what is going on with them. As physicians, our job is to really listen and be open to learning what else might be going on, then formulate that information into an actionable plan.”

Dr. Kathryn A. Gibson, ARUP Family Health Clinic

Chris scheduled his appointments two to three weeks apart, packing several into one day because the effort of undergoing them exhausted him. Every time he did anything that involved physical, mental, or emotional stress, he would crash and feel wiped out for several weeks.

“My life was disappearing before my eyes,” said Chris, a soft-spoken man who is more likely to listen than to be the one talking in a conversation. “Here I was, surrounded by the best, but no one could figure out what was wrong.”

He and Alicia spent their time scouring PubMed and Google, digging into medical literature, and searching for answers. “We didn’t watch TV at night or go out. Ever. We would put the kids to bed, and then we would go to work,” recalled Alicia, who was also working part time and caring for their children. “I felt like my whole future was collapsing in front of me.” She realized she might have to care for Chris long term and provide for her family on her own, so she began studying for the law school aptitute test (LSAT) in order to apply to law schools.

After 12 months of testing, Chris received a final diagnosis: chronic fatigue syndrome and fibromyalgia. There would be no more tests. He was prescribed cognitive behavioral therapy.

“I felt like they were throwing in the towel, giving up on me,” remembered Chris. “I knew this was a diagnosis widely used when physicians can’t figure out what’s wrong.” Despite his deep discouragement, Chris chose resolve. “I knew I would have to be the one to figure it out.”

A Stroke of Luck

Almost 12 months after his bout with strep throat, a friend offered to fly Chris out to Utah to meet with Danny Purser, MD, a family physician who had a hunch after hearing about Chris’s condition. At one point, Purser had also been diagnosed with chronic fatigue syndrome. “I was desperate and running out of hope at that point,” recalled Chris. So he flew west.

Team huddle in ARUP’s Automated Endocrinology Lab.

Purser ran the same panel of endocrine tests that Chris had undergone six months into his illness. “I wanted to do the test but control some of the variables in hopes of a purer result,” said Purser. This required asking Chris to fast for 48 hours, stop taking current medications, and refrain from any activity.

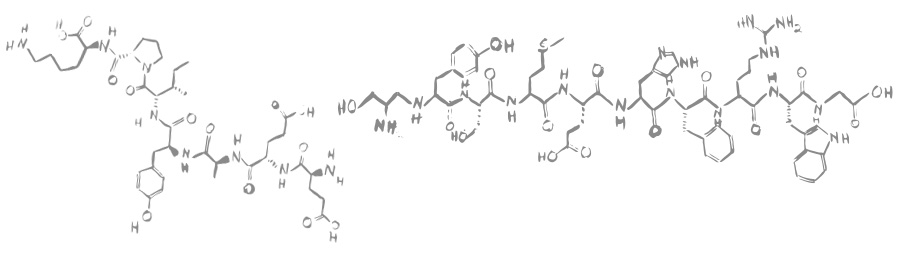

The results showed that a hormone, insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), was on the low end of the normal range (the same results as the earlier test). IGF-1 is a primary mediator of human growth hormone (HGH). Purser suggested that Chris investigate this further and sent him back home with instructions to seek out a well-known endocrinologist at the Mayo Clinic and request an insulin-tolerance test. The test would help clinicians see whether his hormones were working properly.

The endocrinologist reran the endocrine panel with the same results. He told Chris that he did not think the insulin-tolerance test was necessary. Chris pressed him for it, indicating that he would go elsewhere for the test if necessary. Performed in only a few places around the country, the insulin-tolerance test can be risky and requires an inpatient setting.

A week later, Chris lay in a clinic bed and received an injection of insulin. Over the next two hours, his glucose levels were monitored every five minutes, with blood draws every half hour. When his levels dipped below 45 mg/dL, nurses insisted he drink some juice, repeatedly asking him if he was okay. Typical glucose levels hover around 100 mg/dL, and hypoglycemia symptoms start to become apparent when levels drop below approximately 50 mg/dL. “This is how I always feel,” said Chris. His levels would eventually bottom out at 22 mg/dL.

Insulin helps move glucose from the blood into the cells. A low blood glucose state triggers a stress response in the body, making it release hormones that raise glucose levels, such as growth hormone, cortisol, and adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH).

A graph showing these responses usually resembles an elongated bell curve. Chris’s graph had only downward-sloping lines, symbolizing the inactivity of cortisol and growth hormone. “My body was not making hormones when under stress,” said Chris. “We now knew that something was going on in connection with my pituitary gland.”

Pea-sized and tucked at the base of the brain, behind the nose, the pituitary gland is the master of all hormones. Imagine it as the first domino in a Rube Goldberg machine, setting off a complex, multipath chain reaction throughout the body.

“The pituitary gland is responsible for a cascade of hormonal processes that are connected to many different functions in our bodies, from bone growth to blood pressure to thyroid function, to name a few,” said Joely Straseski, PhD, MS, medical director of endocrinology at ARUP. The many different hormonal processes contribute to the complexity of endocrine testing.

However, for Chris, more was at play than just the function of his pituitary gland.

Chris started treatment to correct his low cortisol levels, but it made him feel worse. After a month, he stopped taking it. Then the endocrinologist suggested he try HGH treatment for a year. This required Chris to inject himself with a synthetic growth hormone each night before bed.

“The doctor didn’t have a lot of faith that this would make much of a difference,” recalled Chris. But within one week, he could walk around the house without assistance. Within one month, he was running a mile. “It was like I was being given a new life.”

After 18 months of searching for answers, Chris’s final diagnosis was adult-onset idiopathic pituitary dysfunction. “Basically, we know something is wrong with my pituitary gland, but there is no diagnosis as to exactly what or why,” said Chris.

In the End, a Blessing in Disguise

To catch up on life and to regain his strength, Chris started setting physical goals, including off-road triathlons and a marathon. He returned to work with plans to pursue a master’s degree in laboratory medicine and biomedical technology. His case caught the interest of medical colleagues, who asked him to present to medical students. A professor who taught laboratory medicine and pathology classes changed her curriculum based on Chris’s experience. He and his family returned to Salt Lake City, where Chris took a job with ARUP Laboratories.

Life was blossoming once more for the Allens. On January 11, 2013, Alicia and Chris welcomed their third child into the world. Baby Nicole arrived weighing 7 pounds, 14 ounces. But at 3 months, she started slipping down the growth and weight charts, and her health continued to decline over the course of her first year. “She was lethargic and had problems sleeping and was irritable,” recalled Alicia. Nicole also exhibited unusual symptoms, turning blue in a warm bathtub and shivering uncontrollably.

“I just knew she was in pain,” said Chris, who, along with his wife, began to suspect that Nicole had the same hormone deficiency as Chris. Endocrinology testing confirmed that she lacked the ability to produce HGH. Because of her father’s long journey to diagnosis, clinicians were able to arrive much more quickly at answers in Nicole’s case.

Now, each evening at the Allen household in a suburb of Salt Lake City, Alicia and Chris announce, “It’s bedtime! Come get your vitamins and medicine.” All four children (Ryan arrived in 2015) receive their vitamins, and 6-year-old Nicole receives an HGH shot, which is sometimes administered by her sister Taylor. If you ask her why she needs a shot, she’ll exclaim, “Because I’m special, like Daddy.” (Flu shots are a walk in the park for her.) Chris also takes his shot at night because that is when the human body naturally releases HGH—hence the saying, “Go to sleep so you can grow taller.”

At the ARUP Family Health Clinic, family physician Katherine Gibson, MD, monitors Chris and Nicole closely with regular endocrine testing to check their growth hormone levels, as well as levels of other hormones produced by the thyroid and pituitary glands. She said, “The slightest imbalance in these hormones can have a potent effect on the body.”

Although Chris and Nicole finally received a correct diagnosis, there are still unanswered questions. If a strep infection triggered the HGH dysfunction, as Chris suspects, then what triggered it in Nicole? What is the specific genetic variation responsible for the condition? Could the cause be an environmental exposure of some sort?

Chris, whose master’s thesis focused on HGH and chronic fatigue syndrome, believes epigenetics played a role. “I think it is a genetic trait that gets triggered by a stressor. Mine was strep. For my daughter, maybe it was the trauma of being born.” He is not aware of anyone else in his family who struggled with hormone deficiency or a mysterious illness.

While for Chris, this medical odyssey was both maddening and painful, there is a sense of relief, too. “I’m so glad it was me and not my daughter that went through the struggle of figuring out what was wrong.”

What’s Normal in Hormone Testing?

Some lab tests provide a simple negative or positive answer (e.g., you either test positive or negative for strep throat). Other tests, like those used to detect hormones (endocrine tests), provide a numerical range that defines a normal value for that test. This is called a reference range or interval.

Different laboratories often determine their own reference ranges, so endocrine test results might be reported as normal from one lab and abnormal from another lab.

“Reference intervals show us what results can be expected from a healthy population for a specific hormone,” explained Joely Straseski, PhD, MS, ARUP medical director of endocrinology. Reference ranges help describe what is typical for a particular group of people based on age, sex, pregnancy, body mass index (BMI), and many other possible factors.

The upper and lower limits of the interval are based on the most frequent results observed within that population, providing a reference for comparison. However, if someone’s hormone levels fall just outside the normal range, it does not necessarily mean there is a problem.

Treat the Patient, Not the Results

“I advise clinicians that even if a value is within the reference interval, there could still be a clinically relevant change going on in a patient. The reverse is also true: Values just outside of the reference interval might not have clinical implications,” explained Straseski, who is also an associate professor of pathology at the University of Utah School of Medicine. “Results should always be interpreted within the context of the patient’s clinical history.” For example, if a patient’s testosterone level suddenly drops from 700 ng/dL to 300 ng/dL, it might be a red flag for this particular patient even though the value falls within the reference range.

The ranges for test results in healthy people and those with illnesses often overlap; there isn’t always a clear dividing line. Because of this, the reference range is a guide and not a rigid definition of normality.

Another variable to consider is how dynamic our bodies are—not unlike a boat on moving water, the human body is constantly trying to find equilibrium. “Your body works super hard every day, every minute, to regulate itself, and if you test it at one moment in time, the results could look inappropriately normal or abnormal,” explained Straseski.

There Is No “One” Hormone Test

When physicians suspect an issue with the endocrine system, one of the areas they investigate may be pituitary function. The pituitary gland is the catalyst for most of the hormonal processes and pathways that take place elsewhere in our bodies. It lies at the base of the brain, just behind the bridge of the nose, and can wreak such havoc that it is routine to test patients after brain surgeries to make sure that the gland was not damaged.“Hormones regulate a wide variety of functions within our bodies,” said Straseski. “We have lab tests to investigate the individual steps in these pathways because every step is relevant.” Usually, a pituitary issue affects multiple processes, not just one.

In the Automated Endocrinology Laboratory—one of several ARUP labs that perform endocrine testing—laboratorians work around the clock testing serum samples to analyze hormones such as insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), human growth hormone (HGH), and one of the major IGF binding proteins, IGF-BP3 (insulin-like growth factor binding protein 3).

“The test results generated by our laboratory help physicians determine if HGH is being adequately secreted or if it is suppressed,” said lab supervisor Pete Middleton. “HGH concentrations are susceptible to variation throughout the day and are affected by exercise, stress, and other influences.” For this reason, IGF-1 or IGF-BP3 can provide a clearer picture of HGH production than HGH levels themselves.

While many pediatric endocrine test specimens come to ARUP, ARUP has developed HGH and IGF-1 reference ranges that apply to patients well into adulthood. As Middleton added, “HGH isn’t just important for our initial development, it is important throughout our entire lifespan.”

HOME

HOME